Report: Power of the Disability Vote Across Southern Swing States

A Collaborative Report by New Disabled South Rising and Disability Culture Lab Action

Executive Summary and Introduction

Disabled voters are a critical constituency in the 2024 elections, but this core group of voters has been under researched, undercounted, and barely invested in by campaigns or parties. In this new collaborative study – released by New Disabled South Rising and Disability Culture Lab Action – we find this underinvestment to be a critical misstep by both major parties and any major candidate looking to win in November. With weeks to go until election day – there is no time to spare.

The disabled electorate is a significant and under-accessed voting bloc, particularly important in closely contested southern states. Recognizing the power of the disability vote, engaging disabled voters, and working to grow disabled power will be crucial to electoral success both this year and long into the future.

Disabled voters have incredible power in this election. Our research finds:

Disabled voters are a critical constituency in every major southern swing state.

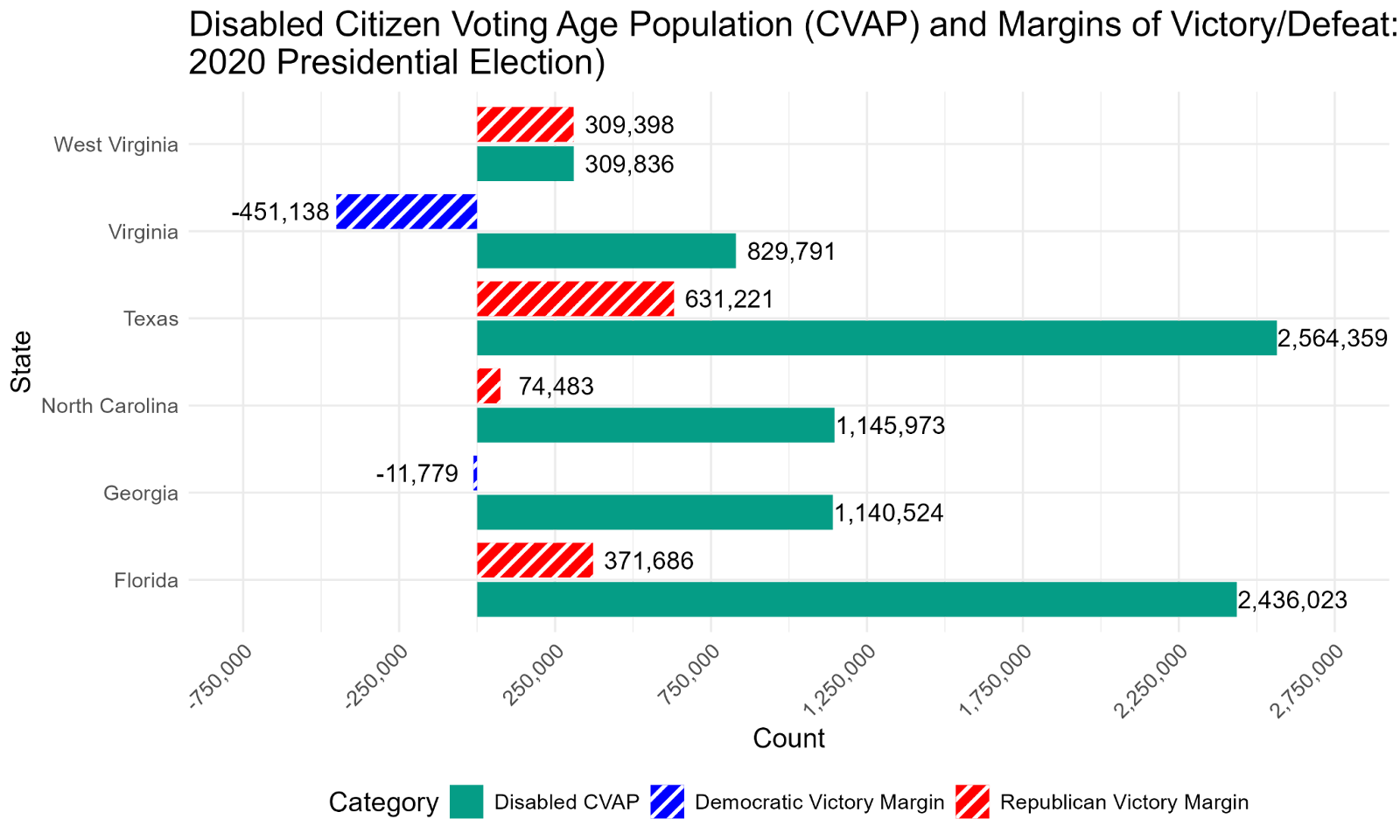

In four critical Presidential swing states across the South – Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, and Florida – the population of eligible disabled voters far exceeded the margin of victory across the last four presidential elections.

In those same states, disabled voters who didn’t vote also exceeded the margin of presidential victory, suggesting that greater engagement could transform elections.

In West Virginia and Texas - two crucial states that will decide control of the Senate - disabled voters far surpass the margin of victory of the 2018 Senate elections.

Our research found that disabled voters far surpass margins of victory in key Presidential and Senate swing states. As a result, we believe targeted outreach programs – from persuasion to get out the vote – to disabled voters by any candidate or party could transform the politics of many of these states.

The Power of the Disability Vote

The disabled voting population is both large and electorally significant. The CDC estimates the proportion of disabled adults in the US at 1 in 4 – comprising over 70 million people as of 2022. For the purposes of this study, however, we have to rely on the American Community Survey (ACS) which has a large sample permitting detailed estimates of the disability electorate, and a definition of disability compatible with voting data from the Current Population Survey (CPS). Unfortunately, the questions the ACS uses to measure disability under-counts it by as much as 20 percent. This means, if anything, that the data here understate the power and importance of the disability vote. Even based on these less robust counts – disabled voters comprise more than 17 percent of the national Citizen Voting Age Population (CVAP), and nearly 18 percent in the South. This segment of the electorate represents a substantial voting bloc that is and has been decisive in critical swing states across the South year after year.

This chart displays the estimated count of disabled individuals in the Citizen Voting Age Population (CVAP) in southern states during the 2020 presidential election. It shows the margin of victory or defeat for the Republican presidential ticket during the election, with Republican victories in red and Democratic victories in blue. Source: American Community Survey.

In both West Virginia and Texas—two pivotal states that will determine control of the U.S. Senate—disabled voters could hold the key to victory. In West Virginia, there are over 328,000 eligible disabled voters, a group larger than the state's 2020 presidential margin of victory. While more than 165,000 disabled voters cast ballots in that election, nearly an equal number—around 163,000—did not vote, representing a significant untapped electoral force. Given that the margin of victory in the last competitive Senate race in 2018 was 19,397 votes, these voters have incredible power.

In Texas, the stakes are even higher. While more than 1.7 million disabled Texans voted in 2020, even the 1.4 million disabled citizens who stayed home that year were more than double the margin of victory in the presidential race. With such a large number of eligible but unengaged voters, the disabled electorate in Texas holds the potential to swing the outcome of any close Senate contest. When looking at the Senate margins of victory, the data gets even more clear: Ted Cruz’s last Senate race in 2018 was decided by just 214,921 votes.

Given the numbers of disabled voters compared to the margin of victory – our data suggests a clear, consistent strategy to engage these voters – from persuasion to turnout – could dramatically shift the outcome of a Texas Senate race.

This chart displays the estimated count of disabled individuals who voted in southern states during the 2020 presidential election. It shows the margin of victory or defeat for the Republican presidential ticket during the election, with Republican victories in red and Democratic victories in blue. Source: Current Population Survey; American Community Survey.

Further, the percentage of the overall CVAP that is disabled has increased modestly but detectably since 2018, when 16.0 percent of men and 16.6 percent of women self-reported a disability. In 2022 those numbers were 16.6 percent for men and 17.5 percent for women. This may reflect composition effects as the population ages, but may also be related to the long-run impact of Covid-19, which has altered the landscape of American disability in ways the data are only beginning to reflect.

The demographics of the disabled electorate reveal important insights into who these voters are and how their voting patterns may differ from the general population. Among the CVAP, disability is distributed fairly equally across gender, with women reporting disability between 0.5 and 1 percentage point more frequently than men (in 2022 in the South, the rate of self-reported disability among CVAP women was 18.2 percent, while for men the percentage was 17.7, with the gap slightly larger in other regions). No specific data was available for transgender, nonbinary, or gender expansive disabled voters.

Self-reported disability within the CVAP does not present with equal frequency across racial and ethnic categories. Respondents who are (non-Hispanic) Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, multiracial, and white report higher degrees of disability than Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander CVAP members. This disparity makes improving access for disabled voters a crucial component of racial equity. Ensuring that disabled voters of all racial and ethnic backgrounds have equal access to voting is not only a matter of civil rights but also a key component of any effort to mobilize the full electorate.

The Data

The analysis in this memo draws on data from two key sources: the 1-year American Community Survey (ACS) and the Current Population Survey (CPS) Voter Supplement. The ACS, conducted annually by the U.S. Census Bureau, allows for detailed state-level estimates of the Citizen Voting Age Population (CVAP) disaggregated by key demographic factors, including race, ethnicity, gender, and income. It is again important to note that the ACS disability questions undercount the true rate of disability by as much as 20 percent, relative to more complete and sensitive measures. According to the ACS, 17 percent of the national CVAP is disabled, 18 percent in the South.

The CPS Voter Supplement, also conducted by the Census Bureau, is a specialized survey that collects data on voter turnout, registration, and reasons for not voting in national elections. The CPS Voter Supplement shows that in the 2020 election, the national turnout rate among disabled voters was 58 percent, compared to nearly 70 percent for non-disabled voters. This supplement is particularly valuable for identifying trends in turnout among disabled and non-disabled voters, as well as for understanding the barriers that prevent voters from casting their ballots.

Barriers to the Ballot

Historical trends in turnout rates among disabled versus non-disabled voters reveal a persistent and troubling gap that has significant implications for electoral outcomes. Numerous studies have documented this disparity, showing that disabled voters consistently participate at lower rates than their non-disabled counterparts. In the 2020 election, the national turnout rate for disabled voters was 58 percent, compared to nearly 70 percent for non-disabled voters; a difference of 11 percentage points. This gap is particularly pronounced during presidential election years, when voter turnout is generally higher across the board. Despite increased political engagement during these cycles, the turnout gap between disabled and non-disabled voters remains stubbornly wide. According to survey data from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission and Rutgers University, more than 11 percent of voters with disabilities - nearly two million people - said they faced difficulties voting in 2020. This suggests that systemic barriers continue to impede the full participation of disabled individuals in the electoral process.

Regional differences in the turnout gap between disabled and non-disabled voters are stark, with some areas showing more significant disparities than others. The South, in particular, has some of the largest turnout gaps, surpassed only by the Northeast in some recent elections. This regional variation underscores the importance of tailoring voter outreach and accessibility efforts to the specific challenges faced by disabled voters in different parts of the country. In the South, where the disabled electorate comprises a larger share of the population, addressing these turnout gaps is especially critical. At the state level, the turnout gap can vary widely, with some states showing relatively small differences while others exhibit much larger gaps. Several nationally crucial states, including Virginia, Georgia, and North Carolina, show turnout gaps of between 10 and 20 percentage points. The party that can narrow this gap among its voters stands to gain tens of thousands of votes in states where hundreds could decide the outcome.

This chart displays the reasons registered voters who did not vote in 2020 gave for their deciding not to vote. Respondents could select more than one reason. Bars displayed in green are reasons more likely to be selected by disabled respondents, relative to non-disabled respondents. Source: Current Population Survey.

The 2020 election brought to light several key barriers that disproportionately affected disabled voters. Among these, illness or disability was by far the largest issue cited by disabled voters, with 33 percent of disabled non-voters reporting it as the main reason for not voting. This underscores the direct impact of health-related challenges on voter participation. Transportation problems were reported by 4 percent of disabled non-voters (higher than their non-disabled counterparts), and COVID-19 concerns by another 6 percent. In contrast, non-disabled voters were more likely to cite reasons such as not being interested (19 percent), being too busy (16 percent) and/or disliking the relevant candidates (12 percent). These differences in the reasons for not voting underscore the unique challenges that disabled voters face, which are often directly related to their disability status. By limiting the ability of disabled individuals to participate in elections, these obstacles not only reduce overall voter turnout but also skew the electorate away from representing the full diversity of the population. The impact of these barriers is particularly pronounced in regions or states where the turnout gap is already large, further entrenching disparities in voter participation. Addressing these barriers, therefore, is crucial for closing the turnout gap and ensuring that disabled voters have an equal voice in the electoral process.

Gaps in Our Knowledge

Major publicly-available surveys that are essential for understanding the American electorate often overlook disability-related questions, creating a significant gap in our knowledge of disabled Americans' political priorities and behaviors. Benchmark surveys like the Cooperative Election Study (CES) and the American National Election Study (ANES), which are crucial tools for tracking partisanship, issue priorities, and electoral behavior, fail to include questions about disability. Meanwhile, even the ACS appears to substantially undercount disabled Americans, leading to data that doesn’t account for the true power of the disability vote.

This oversight leaves researchers with limited data on the political concerns and voting patterns, or power of disabled Americans, a substantial and diverse demographic. As a result, our understanding of the American electorate remains incomplete, potentially skewing policy discussions and electoral strategies away from the needs and preferences of this important segment of the population.

It is imperative that researchers, policymakers, and survey designers prioritize the inclusion of disability-specific questions in these influential surveys. By gathering more comprehensive data on disabled voters, we can make this significant portion of the electorate more visible to elected officials, campaign workers, and the public at large, ensuring their voices are heard and their needs are addressed in the political process.

Conclusions and Key Takeaways

The disability vote represents a substantial and influential voting bloc whose needs and preferences are essential to any candidate or political party looking for a path to victory in the 2024 election.

Our recommendations:

Political candidates and parties looking for a path to victory in 2024 and beyond should invest heavily in disability voter policy platforms, accessible communications, outreach, persuasion, and turnout.

Address the research gap: we call on every national study of US elections to include disability demographic questions – the Cooperative Election Study and the American National Election Study in particular. Academics and election specialists will continue to leave disabled people out as long as we are absent in the data.

State and city governments should tear down barriers to vote for disabled folks who report voting at lower levels because of extreme barriers, especially across the South. It’s time for a Disabled Voter Bill of Rights.

Despite significant numbers, disabled voters continue to face systemic barriers that result in lower turnout rates compared to their non-disabled counterparts. These challenges are particularly acute in the South, where the disabled population comprises a larger share of the electorate and where the turnout gap between disabled and non-disabled voters is among the largest in the country.

The data presented in this memo underscores the importance of addressing these barriers to ensure that disabled voters have equal access to the ballot, democracy, and representation in government.

By identifying and addressing the specific challenges faced by disabled voters, particularly in regions with large turnout gaps, policymakers and advocacy groups can work to close the turnout gap and ensure that the disabled electorate is fully represented.

The stakes are high: in close elections, the votes of disabled individuals are decisive, making it all the more urgent to eliminate barriers to their full participation in the democratic process.

Ensuring disabled voters have equal voting access is not only a matter of equity but also a strategic imperative for any candidate or party seeking to win in 2024.

The disabled electorate is large, growing, and potentially decisive, particularly in the South, where electoral margins are often razor-thin. Addressing the barriers faced by disabled voters is not only the right thing to do; it is also essential for the health and integrity of our democracy.

Authors:

This report is authored by Matt Eckel and Kiana Jackson.

Matt Eckel is a quantitative researcher with a focus on social and economic empowerment, specializing in econometrics, public policy analysis, and survey research. With over a decade of experience, he has conducted research on workforce development, political equity, education policy, and financial health. Matthew teaches graduate-level quantitative methods at Johns Hopkins University. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from McGill University and a Master of Arts in Social Science from the University of Chicago.

Kiana Jackson serves as the Director of Data and Research of New Disabled South Rising. Kiana has spent her career working in rural and minority communities to build capacity for grassroots organizations and empower communities at large. She brings over five years of community organizing experience, data analytics skills, and research expertise.

Throughout her time in community advocacy, Kiana has served as a Data Consultant and Data Strategist for local political campaigns and nonprofit organizations in South Georgia. She has a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from Albany State University and a Masters of Science in Data Analytics and Policy from Johns Hopkins University. She currently resides in Tallahassee, Florida.

New Disabled South Rising is the political 501(c)(4) arm of New Disabled South, the first and only regional disability organization. NDSR fights for political power and liberatory policy for disabled people in the U.S. South. NDSR exists to build and expand the power of disabled voters in the U.S. South through research, polling, organizing, and education. In the fight for accessible policy, elections, and politics for all disabled people, New Disabled South Rising envisions a U.S. South where disabled people live joyful and liberated lives with full political freedom and representation.

Disability Culture Lab Action (DCLA) is a nonprofit disability media and narrative lab that builds the power of the disability community and works to shift the narrative on disability from fear and pity to solidarity and liberation. DCLA provides strategic political communications support by and for the disability community. DCLA is a fiscally sponsored project of Proteus Action League.

Appendix A: Measurement and definition of disability

The American Community Survey (ACS) collects disability-related data through a series of questions known as the "ACS-6" questions. These questions are designed to identify whether individuals have specific types of disabilities.

Questions Asked in the ACS:

Hearing Disability: Can you hear and understand what people say without difficulty? (Options: Yes, No)

Vision Disability: Do you have difficulty seeing even when wearing glasses or contact lenses? (Options: Yes, No)

Cognitive Disability: Do you have difficulty remembering, concentrating, or making decisions? (Options: Yes, No)

Ambulatory Disability: Do you have difficulty walking or climbing stairs? (Options: Yes, No)

Self-Care Disability: Do you have difficulty dressing or bathing yourself? (Options: Yes, No)

Independent Living Disability: Do you have difficulty doing errands alone, such as visiting a doctor's office or shopping? (Options: Yes, No)

Classification: A respondent is classified as having a disability if they respond "Yes" to any of the above questions. The ACS collects this information to better understand the needs and challenges faced by individuals with disabilities across the United States. It bears mentioning that ACS estimates of disability are often somewhat lower than those published by the CDC based on their Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey, which reports national rates of disability closer to 1 in 4 American adults, rather than roughly 1 in 5 as reported by the ACS. These discrepancies may have to do with the mode of survey collection, as well as the nature of the questions, which may undercount certain mental health concerns or disabilities the severity of which changes with time. The ACS has acknowledged the need to rethink the way it measures disability, and it is likely that rates of disability reported here are in fact lower than those that prevail nationally.

The Current Population Survey (CPS) includes questions on disability that align with the ACS-6 questions but are adapted for the survey's format and objectives.

Questions Asked in the CPS:

Hearing Difficulty: Does this person have serious difficulty hearing? (Options: Yes, No)

Vision Difficulty: Does this person have serious difficulty seeing, even when wearing glasses? (Options: Yes, No)

Cognitive Difficulty: Because of a physical, mental, or emotional condition, does this person have serious difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions? (Options: Yes, No)

Ambulatory Difficulty: Because of a physical condition, does this person have serious difficulty walking or climbing stairs? (Options: Yes, No)

Self-Care Difficulty: Does this person have difficulty dressing or bathing? (Options: Yes, No)

Independent Living Difficulty: Because of a physical, mental, or emotional condition, does this person have difficulty doing errands alone, such as visiting a doctor's office or shopping? (Options: Yes, No)

Classification: Similar to the ACS, a respondent is classified as having a disability if they answer "Yes" to any of these questions in the CPS. This data helps in understanding the prevalence and impact of disabilities on individuals' lives and is used for policy-making and program development.

Appendix B: Estimating Turnout

Turnout estimates in this memo are drawn from the Current Population Survey’s Voter Supplement. The estimates themselves, however, are calculated based on different weights than those provided by the CPS. Weights are recalibrated based on a procedure recommended by Hur and Achen (2013) and widely used in contemporary electoral research.

The Hur and Achen correction improves state-level turnout estimates by adjusting for the over-reporting commonly seen in self-reported surveys like the CPS Voter Supplement. While the CPS uses standard weights to make the sample representative of the population, these weights don’t correct for the fact that many respondents claim to have voted when they did not. The Hur and Achen method compares self-reported turnout in the survey to actual state-level turnout figures from official election data. It then reweights the survey responses to match these real turnout rates, correcting the inflated estimates.

This correction is especially useful for analyzing turnout by state and demographics within each state, where the extent of over-reporting can vary. By aligning the survey data with actual election results, the Hur and Achen approach provides more accurate turnout estimates, making it ideal for research focused on state-level voting patterns and demographic differences in turnout.

Sources:

Jean P. Hall, Noelle K. Kurth, Catherine Ipsen, Andrew Myers, and Kelsey Goddard, "Comparing Measures Of Functional Difficulty With Self-Identified Disability: Implications For Health Policy," Health Affairs 41, no. 10 (October 2022), https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00395.

ACS estimates of disability are significantly lower than those published by the CDC based on their Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey, which reports national rates of disability closer to 1 in 4 American adults, rather than roughly 1 in 5 as reported by the ACS. These discrepancies have to do with the mode of survey collection, as well as the way both the ACS and the Current Population Survey (CPS) ask about disability. The ACS has acknowledged the need to rethink the way it measures disability, and that rates of disability reported in the ACS are lower than other more reliable survey methods suggest.

Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Matthew Sobek, Daniel Backman, Annie Chen, Grace Cooper, Stephanie Richards, Renae Rodgers, and Megan Schouweiler. IPUMS USA: Version 15.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2024. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V15.0; see also Sarah Flood, Miriam King, Renae Rodgers, Steven Ruggles, J. Robert Warren, Daniel Backman, Annie Chen, Grace Cooper, Stephanie Richards, Megan Schouweiler, and Michael Westberry. IPUMS CPS: Version 11.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2023. https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V11.0

Jean P. Hall, Noelle K. Kurth, Catherine Ipsen, Andrew Myers, and Kelsey Goddard, "Comparing Measures Of Functional Difficulty With Self-Identified Disability: Implications For Health Policy," Health Affairs 41, no. 10 (October 2022), https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00395.

Lisa Schur, Mason Ameri, and Meera Adya, "Disability, Voter Turnout, and Polling Place Accessibility," Social Science Quarterly 98, no. 5 (November 2017): 1552–1568, https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12373.

Schur, Lisa, and Douglas Kruse. Disability and Voting Accessibility in the 2020 Elections: Final Report on Survey Results Submitted to the Election Assistance Commission. Rutgers University Program for Disability Research, February 16, 2021, www.eac.gov/sites/default/files/voters/Disability_and_voting_accessibility_in_the_2020_elections_final_report_on_survey_results.pdf.

Geiger, N. (2022, October 19). Generating a more accurate, inclusive estimate of disabled people in the US. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/generating-more-accurate-inclusive-estimate-disabled-people-us

Matthew Brault, Sharoultn Stern, and David Raglin, 2006 American Community Survey Content Test Report: Evaluation Report Covering Disability (Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, January 3, 2007), https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2007/acs/2007_Brault_01.pdf.

Aram Hur and Christopher H. Achen, "Coding Voter Turnout Responses in the Current Population Survey," Public Opinion Quarterly 77, no. 4 (Winter 2013): 985–993, https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nft042.